MENSTRUAPPS – How to turn your period into money (for others)

By Natasha Felizi and Joana Varon

Infographic Diana Moreno , Natasha Felizi and Joana Varon

“My freelancer’s dream is for money to show up in my bank account with the same regularity as my period: every 28 days or so. Menstruation is important work for the world. Now that they have figured out how it can make money, it would be great if that money ended up in the hands of the people who actually ovulate and bleed.”

We have monitored menstrual cycles for as long as uteruses have been uteruses. Making money off these cycles, however, is a more recent phenomenon that emerged with the industrial production of tampons and the discovery of hormone synthesis. Period trackers can now be added to the list of inventions that promise women more freedom and convenience. These apps will help you predict your next period and track PMS, plan and avoid pregnancy, and better understand your skin, hair, mood, and appetite.

Menstruapps are among the most popular health-related applications found in app stores. A search for the terms "menstrual cycle," "menstruation," fertility" and "menstrual calendar" brings back 1,116 results (225 after eliminating repetitions). According to researchers at Columbia University, this type of app is the fourth most popular among adults and second most popular among adolescent women in the "health apps" category.

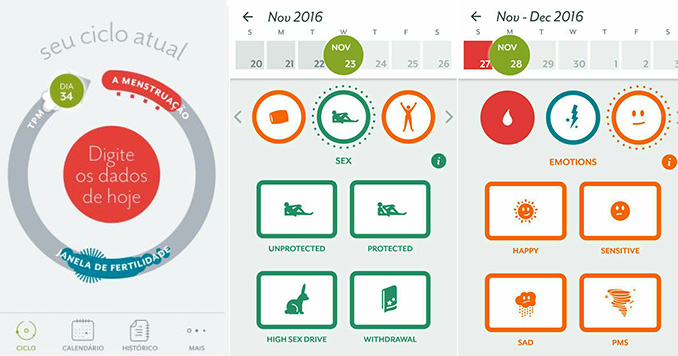

The work of these apps, however goes far beyond that of self-care tools for tracking periods. Monitoring menstrual cycles has also proven to be a promising business model for startups and companies that work with the logic of the Datasucker. The dominant narrative behind these health apps is that of the ‘quantified-self’ movement, which promotes the idea that increased digital monitoring leads to a better life. Feeding on our data, these tools serve as laboratories for observing physiological and behavioral patterns from period frequency and associated symptoms to users’ buying and Internet navigation habits. Monitoring your cycle using a menstruapp means telling the app regularly if you went out, drank, smoked, took medication, got horny, had sex, had an orgasm and in what position, what your poop looked like, if you slept well, if your skin is clear, how you feel, and if your vaginal discharge is green, has a strong odor or looks like cottage cheese.

(Para visualizar melhor, você pode ajustar a imagem ao tamanho da sua tela usando o zoom do seu browser (ctrl+ ou ctrl-)

Crédito da infografia: Diana Moreno, Natasha Feliz e Joana Varon

In an article about how the data and algorithm economy works, Share.Lab compared Facebook to a large factory where algorithms work processing the raw materials of the data we produce when we are liking, sharing photos and visualizing content on the site and producing profiles from them that aid in direct advertising. This model is at work in basically all online services, from emails to menstruapps. Every piece of information that we put online becomes something valuable for companies, making our online activities a key component of their economic survival strategies. If we consider the time that we spend feeding social networks and apps with information as time spent working, the 1 billion Facebook users worldwide are carrying out over 300,000,000 hours of unpaid work per day.

The unpaid work that feeds apps that monitor women's cycles and fertility must be considered in light of the historic lack of recognition for women's sexual, reproductive and relational labor. In "Quantify Everything: A Dream of a Feminist Data Future," Amalia Abreu critiques the logic and the contemporary methods of quantifying life, pointing out that the enthusiasts for the model are, in large part, middle or upper class men. These men and their worldview define the terms around what will be measured and why and whom will be measured and how.

The quantified self movement claims to be designed around criteria that are neutral and applicable to everyone. Aspects of the division of labor that are traditionally understood as feminine -- such as work caring for children and the elderly, the home, or relationships -- are usually not included among the indicators. This is problematic because it reproduces the capitalist tendency to undervalue work carried out by women, caregivers, and domestic workers.

When we turn our reproductive cycles over to apps that operate in this logic, we must stay aware of their terms and conditions. What are we giving them and what do we receive in return? What rules and norms apply to this monitoring? Who designed the apps and set the norms? What values and presumptions orient the evaluations made? What type of knowledge are we producing and who is benefiting? What principles should be observed?

To begin the process of responding to these questions, we analysed the terms of use, privacy policies, marketing strategies and business models of some menstruapps. We choose the those most often downloaded on Google Play and the Apple Store, as well as those that people in our circles and the press most often mentioned. We observed that all of the apps rely on the production and analysis of data for financial sustainability. After being used to calculate the date of the user’s next period, data is also used to orient direct marketing. The data may be shared with other businesses and research institutions or used to inform sales strategies for complimentary products, such as collectors, tampons or thermometers, which, equipped with sensors. Here is an analysis of some of the apps that we are watching:

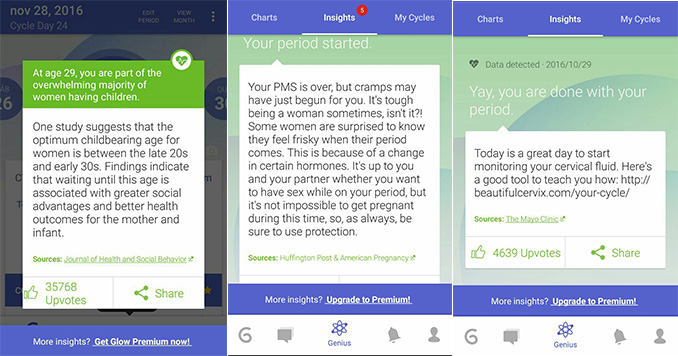

Glow

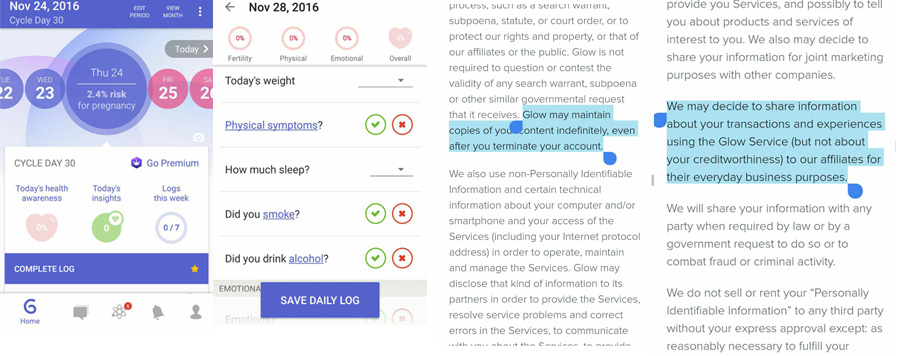

With around 3 million users, Glow has the most frightening business model. Its "ecosystem" is made up of four apps: Eve, Glow, Glow Nurture and Glow Baby. Eve is used to track sexual activity and menstrual cycles. Glow is the most popular and is used to track fertility. Glow Nurture is used during pregnancy, and Glow Baby, to accompany the baby's development after birth. Glow's advertising promises that data analysis can bring clarity around the sexual and reproductive health of both the mother and the child. The company is part of HVF Labs, an incubator for big data projects created by Glow's owner, Max Levchin. According to the HVF site, their objective is to take advantage of potential low cost sensors, the gradual increase in access to broadband, and the high storage capacity to collect and explore "data as a commodity." Data, in other words, that can be commercialized and that has a market value.

Glow's privacy policy states that the company may decide to share information collected on the app with third parties. Data can be used to operate and maintain the app and to inform users about products and services that may interest them. This means that Glow can use the information it receives from users to help its partners meet their business objectives. In other words, even though the data is not sold, the information that this data generates is part of a lucrative business model for the company. The data is so valuable that your content is not deleted, even if you stop using the services,. Data is also used to improve the company's algorithm, which accumulates information in order to become a more and more "intelligent" platform that can later be sold to potential advertisers.

Glow’s privacy policy also states t shared data is made anonymous only in some cases. The text also confirms that it is possible for companies that have contracted Glow for targeted advertising to learn, through embedded cookies, who we are and whether or not we are part of their target population.

Glow also shares our information with companies that provide health and fitness services and that carry out medical research. This proximity to health-related businesses is also part of Glow’s marketing strategy. The paid version of the app promises, for example, that users will succeed in getting pregnant within 10 months. In case of failure, the company promises to pay for fertility treatment.

It is worth remembering that the more data collected about us, the more vulnerable we become. We are exposed not only to ceaseless propaganda, but also to potential leaks of our intimate information. In July of this year, Consumer Reports found a security breach at Glow that let almost any person with a user’s email address access their data and private conversations using the “couple” function.

It is also concerning to note that other successful product of the incubator that created Glow is an app called Affirm, which works like a virtual credit agency. After getting pregnant and seeing so much direct advertising, user’s next need tends to be a loan. With Glow, money making and reproduction have never been so close.

Clue

Advertised as "beautifully scientific," this app has been downloaded around 5 million times in app stores. It opted for charts and tables over the color pink, butterflies and euphemisms. Using phrases like "the future of family planning," Clue is calling for a revolution in women's health. Ida Tin, CEO of Clue, says she wants to promote advances in women's health by contributing to scientific research. Clue shares data with research institutions like Stanford, Columbia, Oxford and Washington University.

Clue was built in Germany, where data protection laws provide above-average protection. At the beginning of its privacy policy, the app displays a link to a text by the CEO about "what it means to have a good-data company." This app does appear above-average when it comes to privacy, as it is one of the few that can be used without creating an account. This means that information can be stored on the user's device rather than on the app's servers. In this case, the app does not have access to the user's data. In cases where users decide to create an account, the privacy policy states that personal information will be stored separate from information about menstrual cycles. In this case, users agree to share data in order to improve Clue's services and contribute anonymous information to clinical and academic research. At any time, users can ask for their accounts to be deleted from the servers.

Security measures around data storage are also described in greater detail. Personal data is encrypted and stored separately from data about menstrual cycles. Since one of the biggest threats to the security of this data is someone gaining access to it through our phones, Clue’s privacy policy also offers security recommendations that encourage users to create a password to protect the app and informs about ways of deleting content if the device is lost.

The interface is ad-free, as the original financing for Clue came from risk-based capital investments. The first round of investments, in 2015, totaled US$10,000,000, of which US$7 million came from Union Square Ventures and Mosaic Ventures. Clue uses cookies and Google Analytics, to track accesses to the platform.

MyCalendar

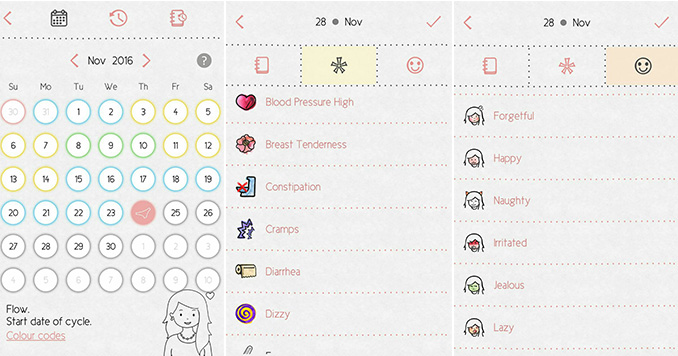

MyCalendar was one of the first apps that appeared when we searched for menstruapps, boasting more than 50 million downloads in the Google Play Store and having been translated into more than 30 languages. The app calculates your chances of becoming pregnant each day, as well as promising to help you with weight control and staying in shape. It covers the complete package of stereotypical women's worries.

MyCalendar was built in Hong Kong and is now advertised under many different names. It requests access to accounts, photos, media, files, vibration control and to network connections on your device. Its privacy policy is short, generic and does not give clear information to its users. It states that the app does not have access to your personal data and that it is not necessary to create an account to use it, however, the app asks for access to the email associated with your app store login. This raises questions about their assertion that they do not have a way of identifying users. Advertising is carried out using Facebook ads, which shows ads based on your navigation history. The app also has an open forum on Google+ and offers the option to export a document with all of your information and send it directly to your doctor.

Maya/ Lovecycles

Created in India, the formerly named Lovecycles is now relaunching as Maya. With 6 million users, developers say they plan to integrate the app with platforms like Google Fit and Apple Health, which is something that apps like Glow and Clue are already doing in order to improve their predictive ability and become the most complete menstruapps in the world. Based in the 'freemium' model, the free version of the app is financed through ads. Users must create an account and give permission for the app to access your location and alendar upon installation. The app can also impede your cell phone from going inactive. A specific privacy policy for the app does not exist, rather it follows the generic terms of use of Plackal, the developer. A paid, ad-free version of the app also exists.

For a more complete comparative analysis of these and many other menstruation, fertility and pregnancy apps, consult the chart developed by Vanessa Rizk and Dalia Othman, of the Tactical Tech Collective, in "QUANTIFYING FERTILITY AND REPRODUCTION THROUGH MOBILE APPS: A Critical Overview," an Arrow for Change publication.

Hardware, the new frontier of the digital pussy

Now that menstruapps have been available for over four years, we are crossing into a new frontier of vaginal digitalization with hardware that connects to them. Described on Kickstarter as the first intelligent menstrual collector, the Looncup measures menstrual blood flow and alerts you on your cell phone, via bluetooth, when your cup is full. It also reports the color and volume of your period. my.Flow has a similar purpose and a very concerning discourse. It seeks to end the "shame of soiling your pants with menstrual blood." We are more concerned about the consequences of a leak of the sensitive data that they collect than of menstrual blood. We also question the idea that menstruation is shameful that they promote. Neither collector is on the market yet and neither organization made the terms of use or privacy policies available for us to evaluate the way they plan to protect or share data.

Also in the pre-launch phase, Kindara is a combination of app and thermometer that indicates better and worse days to conceive. It reinforces the idea that following your cycle is something that can help avoid getting pregnant. However useful this may be, it is irritating that the chief objectives of the apps are to facilitate or avoid pregnancy or to prevent the shame of period stains in women's clothes. After all, many of us are not at risk of becoming pregnant because we are lesbian or trans and period stains on clothes should not considered worse than any other stain. The prevalence of these cliches around menstruation is irritating. Not only do they suck our data to sell us more tampons and moisturizer, they also reinforce heteronormative stereotypes and patriarchal morality.

Not-menstrual leaks

Connected vibrators and diaphragms have been on the market for even longer. They use sensors and process data to provide a “highly personalized experience,” much like Facebook. They advertise increased pleasure and intimacy, as well as the prevention of premature births.

This type of hardware has been responsible for leaks that are much more concerning than blood in underwear. During DefCon in August of this year,, hackers Goldfisk and Follower from New Zealand showed that the smart vibrator We-Vibe 4 Plus collected not only information about temperature and intensity, but also could transmit this information to manufacturers in real time. In some contexts, such as countries where adultery, abortion, homosexuality or the possession of dildos is criminalized, unauthorized access to this information can put lives, freedoms, careers and people’s well being at risk.

Both this case and the episode of the security breach at Glow raise questions about whether or not it is legitimate to collect so much intimate information and how much businesses can actually guarantee the protection of this data. Goldfisk and Follower created a best practices document for connected devices that calls for more transparency and recommends that data, be it from dildos, menstrual collectors or step-trackers, not be collected, transmitted or utilized at all. In the least, people should be able to choose to have their data collected rather than having to choose not to have their data collected. The document was presented to eight companies.

Do I accept?

When we download an app, we sign a sort-of contract saying that we agree to its Privacy Policy. A privacy policy that should be clear and specify what will be done with our information and how. In an ideal world, we would be able to judge whether or not the contract is reasonable or abusive from the information provided. However, the idea of consent has been banalized around the majority of online services. t The privacy policies hide unclear proposals in fine print and often leave us no choice but to accept if we want to use the service. The principle of consent is directly related to physical and psychic protection in queer and feminist circles. Informed consent, when practiced in a situation of equal power, can be understood as a prerequisite for our exercise of self determination and liberty. The patriarchy tends to diminish the concept of consent to simple, non-active resistance, making excuses that tend to legitimize abuses. In the digital realm, companies have pushed this type of not-qualified consent to avoid barriers to the circulation of data about our bodies and the profits they stand to earn.

The good news is that not all hope is lost. This analysis shows that we can work with some of the menstruapps.We can choose the apps that allow us to use them without creating an account, change the privacy settings on our phone and on the app itself to block access to specific data and, in the case of Clue, can choose to store data only on our phone.

But the potential for abuse and for reinforcing the norms of the patriarchy goes far beyond the issue of consent. We should also ask ourselves in what ways the algorithms, sold as mathematical, scientific and neutral, analyze and process information about our bodies? How do they influence the messages, recommendations and alerts that the apps send? What types of 'profiles' are being created about us from the data that we generate when we use the apps? And should it really be considered normal for us to see ads for diet shakes, tips for how to get our husbands back or baby heart monitors all day, every day? How do these messages and incessant ads reinforce patterns of beauty, behavior and sexuality that are a far cry from freedom that they promise, especially considering their popularity among young people?

The history of science on women's bodies is long and complex. And we should question the idea that the best way to observe our menstrual cycles and their relationship with other aspects of our lives is through mere quantification. If the apps are selling themselves as promoters of autonomy and women's self-awareness, users should ask themselves if the awareness they gain is truly freeing or if it is reinforcing stereotypes and prejudices in order to guarantee its scientific and economic viability. At the end of the day, we do not want the same old capitalist and patriarchal discourses to create new ways of making use of our bodies and sexuality to to sell us products and poor ideas about ourselves.

P.S. We are still considering the following questions: what would be a secure and non heteronormative app? If apps for monitoring cycles prove to be efficient contraceptive methods, would this represent an advancement as it relates to hormonal methods? How can e these tools become inclusive of sexual diversity?