Mother in a click: pregnancy as a jackpot for the Datasucker

by Tatiana Dias, Joana Varon and Lucas Teixeira

Collaboration Natasha Felizi

Our online activity is monitored on many levels. This surveillance feeds a lucrative market based on stereotypical profiles, with pregnant women considered the jackpot.

A thirty something woman, living in a big city, working at the intersection of cutting edge technology, news and politics, regularly shopping for clothes, shoes and home decor: this was Carol in a nutshell, that is, up until the home pregnancy test came back positive. But even before the blood test at her doctor's office confirming the pregnancy, and making the big announcement to her family, the online market was already y celebrating the good news -- by pushing an array of online ads for pregnant mothers and babies down her throat.

“Little by little anything that wasn’t related to pregnancy disappeared from my Facebook timeline,” she says. Her online identity became only that of a mother,her entire internet experience was related to maternity. “Pregnant friends with whom I had not been in touch in years started to appear in my timeline.”

But it didn't end there. Spotify suggested a song with the name she chose for her daughter. The name also appeared in personalized advertisements that she saw on the internet. And the day she talked to her friend about the crib set she wanted, and ad for it appeared in her timeline.

After her daughter was born, the nature of the ads changed. Articles about Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, terrifying for any mother, started to appear in Carol’s timeline, followed by ads for equipment to monitor the baby while she slept. They started popping up alongside ads about how to be a “fit mom” and how to “get your husband back after the birth.”

Ad for an after pregnancy corset, which supposes that after giving birth you should worry about the perfect body. And ads when the algorithm goes wrong: filter the term “pregnancy” to view tragedies with babies.

And this is what a large part of society, or at least the people that build Facebook algorithms and other targeted advertising tools, think is appropriate for women who have just had children - a dramatic reflection of a sexist mindset.

More and more of our online experience is personalized based on what we click, what we browse, what we purchase, who we talk to, and many other things that we can’t even imagine. And, in the case of a big life event - like the arrival of a baby - it suddenly becomes clear how online services and advertisers manipulate us in ways we don’t usually notice.

Goodbye woman, hello mother

Companies are interested in understanding people as specific consumer profiles, especially when they are in phases of life where they are more likely to make purchases. This makes pregnant women especially vulnerable to exploitation.

In the era of Big Data, it is estimated that advertisers value the average customer to be worth US$0,10, while a pregnant woman is worth US$1.50.This calculation was made by the American sociologist Janet Vertesi. In 2014, she conducted research on her own life experience and showed that the only way to hide pregnancy from the internet is through anonymous browsing with Tor. Any slip on a common browser, a visit to the Baby Center forum or a search for a "morphologic ultrasound," for example, is enough for a woman to be profiled as pregnant. And, once profiled, companies will not skimp on efforts to win over that consumer with the most targeted advertising possible. Chances are high that the ad will compel her.

"The ads were related to my identity," Carol said, which makes sense because women go through a process of reconstructing their own identity after a child is born. Marketing knows this. It is part of the profiling process, looking for boxes of behavioral patterns and trying to fit people in them, giving them what they want. Or what they think they want.

The problem is that, with the internet, the level of detail and persuasive power of ads reaches levels of consequences that are yet unknown. Advertisers might know, for example, what week of pregnancy the woman is in, or if she is experiencing depression. This level of detail is only possible because of sophisticated monitoring tools that track everything that you do online. Everything.

Wherever you go, I will track you

There are many levels of tracking. The most obvious are in the tools people use. For example, until June 2017, Google used the content of your emails to determine which advertisements to show you. Facebook also displays ads related to our activities on the platform such as likes, the likes of friends, posts and other expressions of interest.

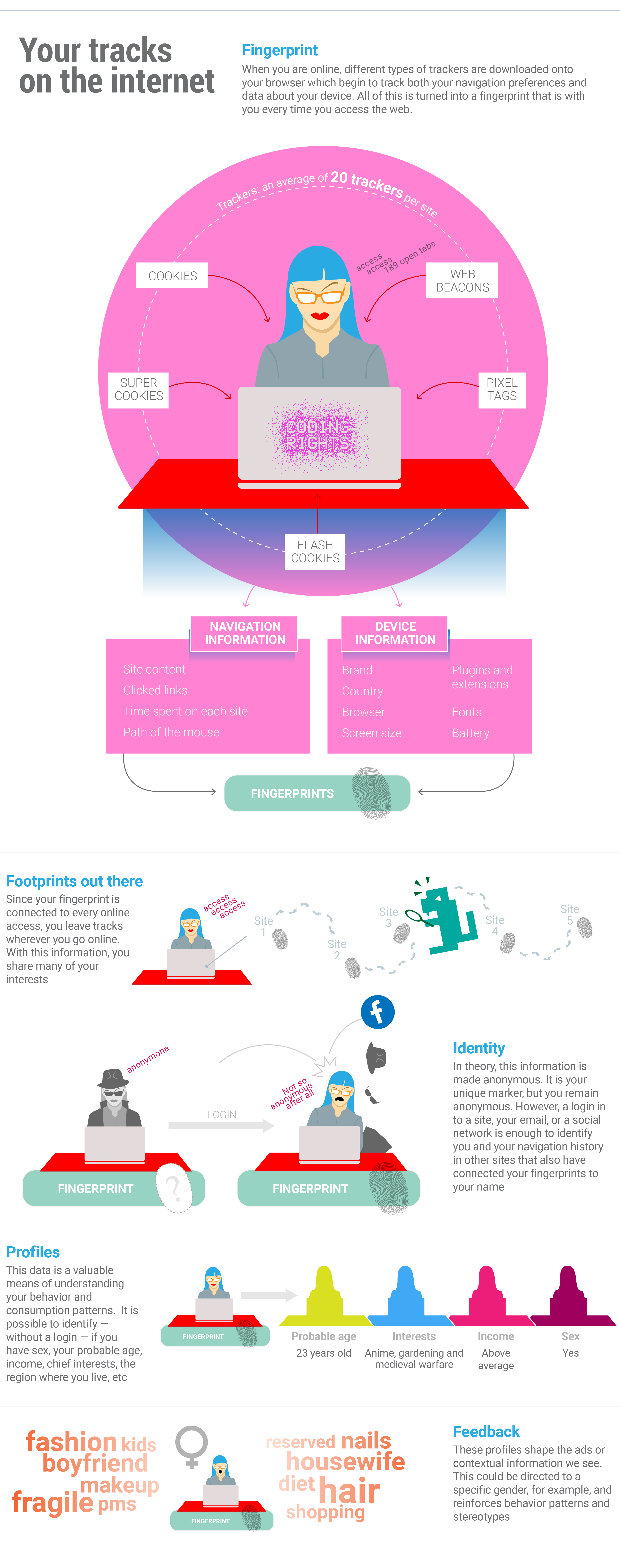

But companies also have another way of collecting data, one that is almost imperceptible to most people: trackers that relay information about the sites you visit. They know how long you stay on a web page, the purchases you make, and even where you hover your mouse. It is no accident that the tennis shoes you are in love with follow you everywhere on the internet. Someday you will be convinced to buy them, right?

The ease of the interfaces and the mystical metaphor of the “cloud” make us think that a stroke of magic happens and takes the data from one place to another. It is not magic and there are tiny spies all along the path.

Every time you access a webpage, you share tons of extra information: the browser you are using, the apps you have installed, where you are accessing the internet from, and even the way you hold your phone your cell phone. The collection of mass datasets is not necessarily due to malevolence, but rather the result of the internet being developed to prioritize connectivity over privacy. The data these technologies collect, however, has become very valuable for industry to better understand potential customers on the other side of the screen.

But the data collection does not stop there. Tracking programs are able to extract a vast array of other information about you and your navigation. As a result,, when Carol accesses a site, her browser does not only download the text and images of the page, but also executes a series of programs embedded in the site in the form of javascript, flash and other script files. These programs are able to access and process data from both the page itself (to create animations, effects and functionalities) and the device you’re using to access it. Tracking companies use all these techniques to monitor Carol's activities online.

Infographisc by: Daniel Roda, Joana Varon and Tatiana Dias

Infographisc by: Daniel Roda, Joana Varon and Tatiana Dias

A recent study by researchers Steve Englehardt and Arvind Narayanan of Princeton University shed some light on the main actors in this industry. Analyzing the top 1 million most visited websites, according to the Alexa ranking - the researchers found tens of millions of different scripts. A small group of companies (like Google, Facebook and Twitter) are present in a large quantity of the sites, which indicates that a few big actors dominate this industry.

The amount of information that can be extracted from browsers is dangerous and in cellphone apps it is even more critical. Apps are able to access information on your device (“but why would a flashlight app need to access my calendar???”). Many apps are also able to collect information even when they are not open.

There is also evidence that companies are monitoring what we write in private WhatsApp messages, as well as what we say near the microphones of our cell phones, computers, and even in proximity of "Internet of things" devices in our homes.

Carol and her husband, for example, would regularly see the same online ads, a coincidence that stopped happening when they both turned off the microphone in the Facebook app on their cell phones.

Anonymous, but only to a point

Companies guarantee that data collection is always done anonymously, but it is possible to identify a specific user in the crowd. When Carol creates an account on a platform and shares her personal data, or enters her cell phone number in an app, it is easy to understand that her logins and actions are connected to her profile. However, companies that make the monitoring platforms have developed methods of identifying people on the web without them even logging in. And, again, this monitoring is done through trackers. It is not an exaggeration to estimate that every website has, on average, 20 trackers following the activities of its users.

Using a technique called fingerprinting, trackers make, as the name suggests, a digital fingerprint of all of the data that they are able to gather about the browser - version, size of the screen, plugins, extensions, APIs, etc. This fingerprint makes it possible to know that the person accessing site X is the same person accessing site Y. And in this way it is possible to know that Carol is a woman, mother, who also likes technology and tends to make online purchases. A login on one of the sites where she has an account is enough and poof, it is possible to connect her navigation history from all of the other sites where she logged in with a username.

At first glance, you might not think this information would be useful. However, there is consensus in the tech community and in computer science that by combining even a little data about someone’s habits or behaviors, it is possible to identify them, or at least to distinguish them from the masses by using collective characteristics like ethnicity, economic situation, health condition and political positions.

“There are only 6.6 billion people in the world, so only 33 bits of information are needed to determine who a person is.” Arvind Narayanan, researcher, on his personal site dedicated to the (de)anonymization of data

There are a number of of techniques that make it possible to cross information from different devices (known as cross device tracking). They show, for example, that a site visit from a laptop came from the same person who used her cell phone to call a taxi - and also to show the same ad on both devices.

Profiles for sale

Identifying your audience is the best way to earn money from it. And profiling is one of the most widely used techniques for this, because patterns and tendencies can be easily extracted from a large volume of information through data mining.

Generally, profiles do not identify anyone individually, but are used to place people in categories. They can be determined by the person who programs an algorithm - a top-down approach - or can emerge from correlations made by crossing attributes from one or more databases and then be interpreted by specialists or professionals in the area - bottom-up.

"The main objective is not to produce knowledge about an identifiable individual, but to use a collection of personal information to act on similarities," says Fernanda Bruno, who has a doctorate in communication and is a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in her book Machines to See, Ways to Be. "The profile acts like a categorization of conduct, attempting to simulate future behaviors."

One of the leaders in this sector in Brazil is Navegg. The company monitors around 400 million people and has scripts in 100,000 sites. Promising clients a “holistic vision of the internet user,” Navegg offers many data intelligence services, behavioral targeting and analyses of navigation profiles.

The company is one of the few in the field that allows the user to check his or her own profile and, if they want, to stop being monitored. This is a good company practice, since in Brazil there is no regulation to limit this type of tracking. The company did not respond to our questions sent, but the site offers relevant information.

Navegg “uses twelve criteria: gender, age, education level, social class, marital status, interests, shopping intentions, behavior, brands, work area, technology (connection, devices, browsers and operating systems) and location (country, city and region)” in order to classify internet users into different categories. Using this model, the company could have analyzed Carol and determined that:

- She falls into the paternity category (“internet users that access content about educating children, caring for babies, pregnancy, among others”) because she visited sites about the meaning of names or searched for symptoms or specific conditions for pregnancy

- She also frequently researches topics related to programming and technology, so she certainly fits the type Software Development (“Internet users that access sites about software development, programming languages, databases, computer networks and information security, etc”).

- Her work in an NGO probably also means that she will be classified in the Social Causes category (“people who access content about social causes, charity, philanthropy, among others”).

Beyond the internet, an entire industry has developed to collect, process and resell data, weaving connections among different databases.These companies are known as data brokers. Buying and selling data generated within and outside the network (like registration in stores, credit protection services and even government social programs), data brokers can generate profiles and segment the population even more precisely. When Carol uses her loyalty card in the grocery store and pharmacy to get a discount (or even when she uses her credit card), this contributes to the offers she later received related to pregnancy products.

Ghosts and stereotypes

Profiles are usually associated with actual people - including pregnant women and babies, but in some cases they don't. For example, in her book “Healthcare and Big Data - Digital Specters and Phantom Objects,” the British sociologist Mary Ebeling describes how the market keeps a baby alive through data, targeted advertising, newsletters and other commercial strategies, even if a woman has a miscarriage.

It is a “marketing baby.” “A baby full of desire,” she says. Desire for clothes, powdered milk, a carseat, storage of stem cells from the umbilical cord and other types of products and services offered incessantly to her mother, even if she was never born. Ebeling, who experienced this personally, collected stories of other women who tried to free themselves, to no avail, of the offers for a child that would no longer be born. There are cases of ¨marketing babies" born out of profiles created in mother’s forums, pharmacy records. In these cases women found it difficult to change the way the way they had been classified and targeted, even when their babies had not been born.

Since there is no control over the way data is collected and shared with third parties, the simple deletion of the account that established the woman's profile as a mother is not enough to change their status. In the book, the author shows how together the complexity of the system and the lack of agency that we have over our own information leads us to be profiled as something we no longer are, or no longer want to be.

While the situations that Ebeling describes demonstrate some of the most cruel aspects of the profiling system, there are other consequences as well. The process creates a vicious circle: once a woman is classified as pregnant, she begins receiving targeted ads illustrating mainstream marketing conceptions of motherhood. It is likely that these ads will shape her experience and behaviour, leading to more of the same advertising.

In the case of maternity, for example, this phenomenon reinforces socially predetermined roles of the woman as the chief caregiver and responsible party for the children (and, after, for getting back the pre-pregnancy body and her own husband, according to the ads that Carol saw). “They do not only provide information that says what we are, but they throw things at us that keep us in that profile,” Carol said.

When Carol noticed the targeted marketing she was receiving, she spoke with the father of the child. Though he had searched for information and products related to paternity and babies, he received almost no advertising targeting parenthood. “I think it is because he is a man,” Carol suggests. The market doesn't consider men to be interested in their children.

“We are only shown things that reinforce the same characteristics. Because this is better for the market. The more clear the profile, the easier it is to sell things.” Carol*, 31, mother and researcher in the area of technology and society.

Women are historically classified and represented in a way that serves, to a certain extent, the patriarchy. Be it as sexual objects or fulfilling a specific role - mother, grandmother or successful professional -, the feminine representation is always connected to stereotypes, with little space for complexity. “Technology makes something that society already has worse. All of a sudden I became a woman who does not want to know anymore about politics and technology”, Carol says.

How to get around all of this monitoring

In countries like Brazil we do not yet have an overarching law protecting personal data, which makes it even more difficult to know what type of information companies are storing about us. But the situation could change: congress is discussing PL5276/16, a draft bill about data protection that would potentially solve some of these issues.At least, if approved, the law would at least request that data are used with informed consent and following some principles such as the finality, necessity and proportionality (in other words, your data can only be used for the end you have provided it). It would also provide for a watchdog mechanism and reparations if harm is done.

To help us push this project, the Network Rights Coalition is mobilizing and sharing information using the hashtag #SeusDadosSãoVoce (your data is you) - follow and collaborate by sharing and helping more people to understand the importance of the topic.

But, even with or without data protection laws in your country, there are some measures that you can take to protect your browsing:

1. Use ad blockers in your browser. For Android, "Block This" is a free software solution that works across browsers and apps (however, it is not available in the Play Store because Google banned it; install through the site) and AdGuard (free for 14 days). For Firefox, use Privacy Badger e uBlock Origin. For iOS, there is Better (paid, focused on blocking behavioral tracking) and Firefox Focus. For Chrome e Firefox, you can use uBlock Origin or Privacy Badger. For all platforms there is Brave, which in addition to blocking ads and trackers has an alternative method for paying websites;

2. Have separate profiles in your browser for different tasks. Tips on how to do this in Firefox and in Chrome;

3.Restrict Cookies: disable flash cookies ou super cookies in your browser's configurations, activate the cookie self-destruction feature, which destroys cookies as soon as you close the window (just for Firefox);

4. Browse with Tor. Rather than blocking trackers, to anonymize browsing Tor makes it impossible to track your steps back to you. For the computer it can be downloaded at torproject.org; for Android you can install the apps Orfox (o navegador) and Orbot (o proxy);

5. Test. Did you take one of the steps? Test your browser's security using panopticlick.