Chupadados is also taking our kids for a walk

By Tatiana Dias e Joana Varon

Much like social networks, apps and children’s games use data to spy on, manipulate and turn children into consumers before they are even aware.

The pediatrician’s recommendation could not be clearer. Children should only be allowed screen time after they turn two. Here in the real world, however, where adults of all ages, myself included, spend our days absorbed in our cell phones, keeping my children out of contact with them seems like an impossible mission.

Gabi* was one when she played with a cell phone for the first time. She watched a carefully chosen YouTube video. Even though the device is not a part of her everyday routine, sometimes the phone ends up in her hands. Worried that she would start sending random messages or fill my phone memory with selfies, I downloaded the most popular games from the App store and YouTube Kids, which says it gives parents more control over which videos children can access.

It only takes a few minutes. I leave Gabi watching an educational video, let my guard down and go do something else. When I come back, she is watching a very strange unboxing video. For those of you who don’t know, an unboxing is a video of a young youtuber opening a new toy on camera and commenting about the product. It is not hard for a child that watches Peppa Pig find her way to an unboxing of a Peppa Pig toy. Gabi’s little fingers, guided by the algorithm that chooses the next videos she will send, always end up taking her to the unboxing videos and giving her a little taste of subliminal advertising with every “HEYY GUYS!” she hears.

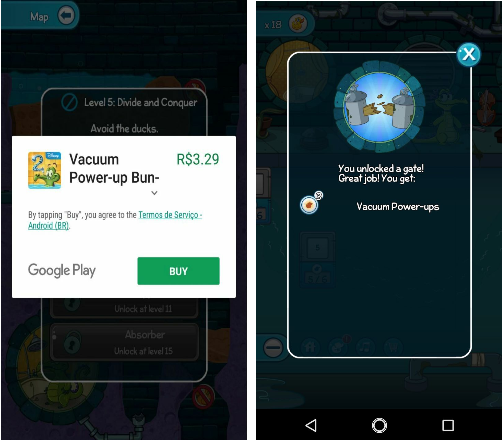

When I got tired of the videos, I turned to apps. Free apps are full of tactics that require in-app purchases (with real money) to keep the game interesting. Food or power needs might need to be bought, for example, to move up a level. Communication around this is always very subtle and in inverse proportion to the excitement around whatever must be purchased. There are many reports of children that racked up charges against their parents because they knew the App Store password or had their fingerprint registered to unlock their parent's phone.

The majority of free games available both on Google Play and on the App Store allow some kind of advertising. In general, developers have no reservations when it comes to including banners in their apps. These banners tend to use information from the device itself to identify and display ads that are chosen specifically for its adult owner. Advertisements for airline tickets, apartments, clothes or anything else that the internet thinks that I want often interrupt Gabi's games. Thankfully I do not shop often for dildos online, right?

What advertisers wouldn’t give to learn children’s preferences

The same mechanisms of monitoring and surveillance at work in the adult world are constantly applied to children online. Whether disguised as marketing or as security measures, they are multi-layered and complex. If we adults are not aware of this complexity, imagine the difficult for a child to recognize the traps and techniques that seek to turn them into early consumers.

Just as businesses want to learn about the preferences and behavioral patterns of adults on the internet, they are eager to get to know their child users. And they use the same techniques of capturing and analyzing massive amounts of data on kids as they do on adults. There is a catch though. If the process of seeking consent from adults around this data is shady, just imagine the levels of abuse and manipulation that threaten children.

The European Commission analyzed 25 of the most popular online games in a study and concluded that "all of the advergames, or games that are financed through advertising, all of the games on social media and half of the app-based games contain ads, some of which are contextual," or directed specifically at the owner of the device.

The impacts of these adds on children go beyond stimulating new desires in children. Research has shown that these techniques and the inadequate content they present, can later appear in the personality and behavior of children.

The European Commission study also used behavioral tests done on children aged 6-12 to demonstrate that this exposure deep, subjective effects. Advergames change the consumption patterns of children. A game full of ads for junk food, for example, increased the levels of consumption of this food in Dutch and Spanish children. The game itself did not change the children's eating habits, rather the ads that were exhibited in it.

"Ads embedded in online games have a subliminal effect on the children, they impact behavior without the children even noticing," the study concludes.

Another study analyzing purchases within the games, showed that all a parent has to do is unlock the in app purchase mechanism and children are easily convinced to buy the bonuses, strength or any other prize available by credit card. The most vulnerable children are eight to nine years old.

Researchers also conducted focus groups with eleven and twelve-year-old children. The children claimed to be able to differentiate propaganda from other types of content. When they were actually exposed to ads, however, the children could not tell them apart.

It is worth mentioning that the legislation in many countries, including some in Latin America, limits ads directed at children. In many Scandinavian countries, for example, all ads that target children are prohibited. In Latin America, there is a growing movement to interpret legislation around publicity for children as abusive content, specifically because it can impact child development and can even bring on health problems like obesity.

When it comes to privacy, there are no clear laws that protect children and their browsing data from the commercial exploitation. We must raise consciousness about the risks we run when we put our children in front of the screen. Our worry is no longer about them speaking with strangers as it is about the strangers that learn their preferences and then manipulate their desires.

Data game

In the United States, mass collection of children's data has resulted in a number of lawsuits. In August of 2017, a California mother sued the Walt Disney Company around their 42 apps and games that monitor children and sell their information to advertisers. According to the plaintiff Amanda Rushing, cellphone games like "Disney Princess Palace Pets," "Toy Story: Story Theater," "Disney Story Central" and "Star Wars: Commander" systematically collected information to create profiles of children that could then be sold to advertisers.

The accusation is based on the Children's Online Privacy Act - COPPA, which restricts advertising practices that target children in the United States. Playdom, a Disney subsidiary, has already paid a fine of 3 million dollars for collecting data from around 1.2 million users online. The majority of these users are children.

Online advertising agencies like Upsight, Unity and Kochava, were also accused in the case for having put software in Disney games that tracks of children's data. The case accuses these agencies of collecting children's geographic location, navigation history and app utilization data, without their parents' consent. This information was later sold to third parties who direct advertising.

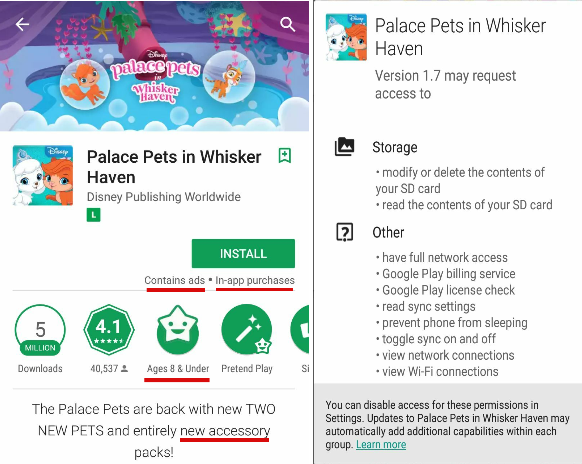

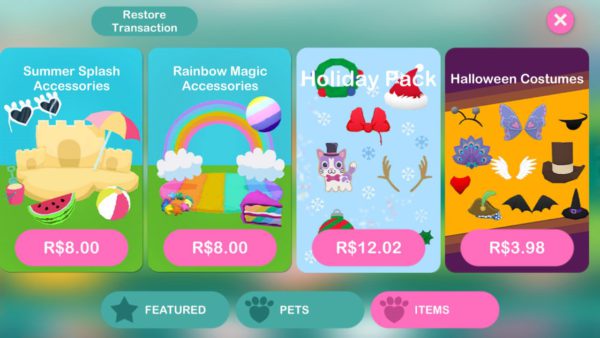

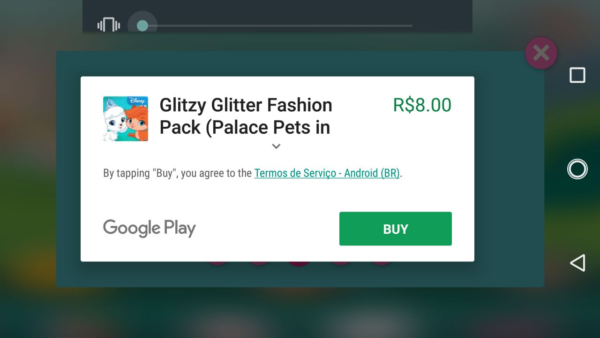

Palace Pets, a game where children can buy pets and accessories for them, has more than 5 million downloads on the Playstore. They are being sued in the United States for violating children’s privacy. In the image above, you can see the warning that the game contains advertising and has an option for in-app purchases underlined in red. It is not really possible to play Palace Pets without spending money. We tried and couldn’t get past the third level.

Even for eight year olds, in this game, a purchase is only a few clicks away. After entering a short series of numbers, children gain access to the page that processes credit card payments.

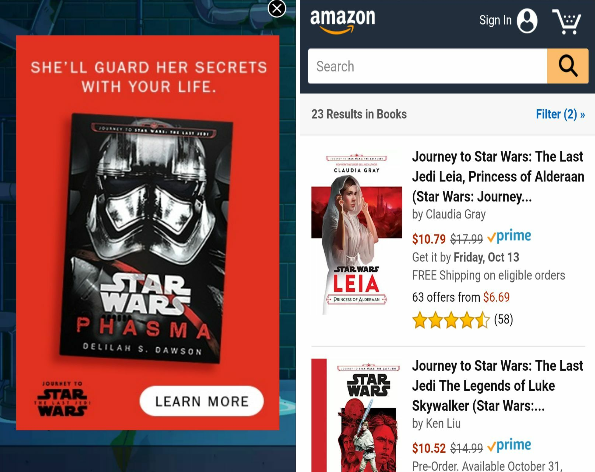

Another game involved in the lawsuit is “Where is my Water 2,” which has more than a million downloads on the PlayStore. On it, direct advertising appears in the middle of the page and when the player clicks “read more,” he or she is taken directly to the Amazon store.

Within the game, there are also ads for tools that help players move to the next level. Spending their parent's’ money, children can collect rubber ducks or help an alligator unclog pipes in order to take a bath.

New skills are unlocked with a purchase. If the player insists on working toward them he or she can, but this seems to have gone out of style.

Star Wars: Commander, another leader with more than 10 million downloads in the PlayStore, is also being sued. In the game, resources can be purchased that help players defeat the Empire. Items cost between US$0.50 and US$110.05 (!).

Treasures are sold that can later be traded for resources for intergalactic warfare.

Even though Disney claims that it respects United States' legislation and that data collection is restricted, in its privacy policy, the company reveals that it does in fact gather data about its users, even children, and shares that information with third parties.

This unparalleled data collection is not just a Disney practice. Older and more famous games like Fruit Ninja, with more than 100 million Playstore downloads, or Talking Tom, with 500 million, both earned a D in the ranking developed by PrivacyGrade. They collect much more information about users than would actually be necessary for them to operate, including information like the user's service provider, their data from Google and Skype and their location. All of this data is collected without clear and explicit parental consent.

Sales on the My Talking Tom app

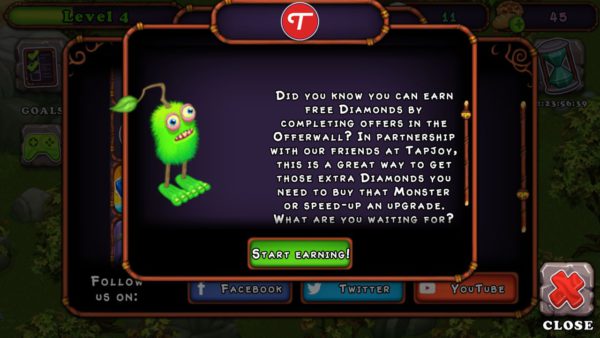

Games like My Singer Monster go above and beyond, turning children into workers in the "like, share and view" factories of the large social networks, feeding their algorithms in order to finance the game. From the outset, players have to create a gamer ID in Google Play Games and throughout the game, there are many opportunities to make purchases, specifically of diamonds to feed the band of little monsters.

It is also possible to get "free money," which is never as free as it seems. My Singer Monster has a partnership with the business Tapjoy, which is dedicated to marketing and the monetization of apps. It collects information about our devices, our location, the ads we see, personal data that third parties collect, including information about our contacts and social networks. It uses this information to drive advertising.

It is possible to earn credits on the game through unpaid work done in the algorithm factories of the big social networks such as viewing the videos of the business on YouTube or by indicating friends on Facebook to play with you. Should a child not want any of that, he or she will still be showered with promotions and discounts on the emeralds. All for a limited time of course.

I have it, not you

On YouTube it is no different. Marketing to children, though often hidden, is alive and well. In a study that collected data on 12,8 thousand videos from 41 popular children's channels in Brazil, the United States and the United Kingdom, researchers found that a majority of the content had some kind of subliminal advertising. The unboxing videos are a great example.

This is especially concerning when we remember that the majority of viewers of these children's channels are, in fact, children. This seems obvious and trivial, but it isn't. In theory, YouTube prohibits users under the age of 13. In other words, there is a large volume of content being made and distributed for an audience that should not even be accessing it in the first place. On YouTube, children are exposed to very high volumes of non-regulated propaganda.

Peppa fake and compound fractures

It is not just the subliminal advertising that concerns us about YouTube. The sites with children's content operate under the same logic as the rest of the internet: algorithms organize content and indicate videos and posts that will likely interest young viewers.

YouTube Kids, which Google launched in order to try to filter content and create a safer space for kids online, operates under a recommendation system similar to that used on the adult site. It considers the videos watched on the platform, as well as viewer's behavior and navigation habits, when making content suggestions. Children, as you know, like to watch the same thing zillions of times over.

Taking advantage of this trend, producers make low-quality videos that are the equal or very similar to one another, immersing children in their own filter bubbles of songs, animals and unboxings. They generate thousands and thousands of views, on loop, and make a profit for the producers. It is no coincidence that it only takes Gabi a few minutes to become trapped in one of these low-quality productions, even when her starting point was a carefully chosen video.

The impacts of filter bubbles on children are still being studied. Researchers suggest that this process prevents children from accessing diverse opinions and topics. It can also guide behavior and reinforce patterns of self-stigmatization or the stigmatization of certain groups.

Peppa Fake is a result of algorithm-guided browsing. Since it is similar to and viewed by the same people that watch the original, it ends up appearing in the recommendation system

An even darker side to all of this can be found in videos with inappropriate content disguised as children's videos. They tend to be just one click away, even on YouTube Kids. Fake Peppa Pigs smoke cigarettes and torture other pigs with dental tools. On the Evil Toy Doctor, patients present compound fractures and injections turn people into zombies. This is not funny, it is disturbing.

Gabi has never found her way to one of these videos, the worst so far have been the unboxings, which are horrible unto themselves. But for safety's sake I took a break from YouTube Kids. And from games. You know that saying that if you don't pay for the product you are the product? Well the same is goes for children. The difference is that adults are responsible for their choices.

Connection watchmen

In Brazil today, 79% of children and adolescents between nine and seventeen years old use the internet. Separating the age groups even further produces surprising results. 63% of nine and ten year-old children accessed the internet in the last three months. By eleven and twelve, this number jumps to 73%, according to TIC Kids, a report produced by the Brazilian Internet Management Committee.

What do these kids do online? They mainly do research for school work, chat with other people, access social networks, download apps, post photos and watch videos. According to TIC Kids, almost 70% of children that use the internet in Brazil are on Facebook. 63% watch videos online.

Of the 100 most popular YouTube channels in Brazil, 36 target children aged twelve and under!

A large number of sites, including Google, YouTube, Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, however, establish a lower age limit of thirteen. In other words, any child under the age of thirteen that uses one of these services is, by definition, disobedient. But the problem here might not be disobedience. Rather it is the rules themselves and who enforces them.

When it comes to risk online, 7% of children between the ages of eleven and twelve accessed pornography, 12% added a friend that they had never seen personally and 14% were treated offensively. Among all of the children and adolescents in the study, 10% have made in-app purchases.

Social networks like Facebook and video sites like YouTube are the chief channels through which children come into contact with advertising on the internet. Six out of ten users between the ages of eleven and seventeen saw advertising on these sites.

A third say they do not like seeing this type of ads, however the results show a different reality. 53% say they have followed or liked the brand advertised and 33% said they asked their parents for the advertised product. Another study, conducted by Nickelodeon in 2012, showed that in decision making about family purchases, 82% of children declared the internet as their chief source of information, beating out television.

In Brazil, advertising directed at children to stimulate consumption is prohibited. There is no specific regulation for the protection of children in online environments, however article 227 of the Federal Constitution, the Consumer's Defense Bill and the Statute of Children and Adolescents determine call advertising directed at children abusive. This vision was reinforced in 2014 with the approval of Resolution 163 by the National Council on the Rights of Children and Adolescents (Conanda). Resolution 163 considers abusive any communication with language directed at children, where children are represented, or that includes any person, presenter, character or doll that appeals to children. It also prohibits advertising that includes prize distribution..

Julia Silva, youtuber mirim brasileira, em um de seus vários vídeos de unboxing

The rules also apply to the internet and the fiscalization and punishment of eventual abuses are the responsibility of the National Council of Publicity Regulation (Conar), an organ that, it is important to remember, previously called Resolution 163 "censure." In practice, Resolution 163 is rarely applied to the internet.

And internet businesses are comfortable following their own resolutions and terms of use. In practice, these have already proven inefficient as networks continue catering to children and making a profit off of them.

Participation and consent

In this context, children regularly access the internet and are exposed to advertising and other types of harmful content hidden in games and educational materials. This impacts their personality formation while internet businesses receive tons of new, younger users, even if for this to happen they must break their own rules. The response seems to be the classic one: prohibit and restrict. At the end of the day there is a lot of danger out there, isn't there?

Many organizations and medical societies have made recommendations along these lines. The Brazilian Pediatric Society, for example, says that babies should be kept completely away from screens until they are two. From two to five years of age, the limit should be one hour per day. In a pamphlet, Brazilian doctors warn about the possible harmful effects of the internet: anxiety, early sexual development, violent behavior and cyberbullying, among other consequences.

In January of 2017, however, a group of 81 researchers from universities including Columbia, Oxford, Berkeley and Harvard published an open letter questioning the "moral panic" and "contemporary anxiety" around the fear of screen time. They argue that there is not enough solid scientific evidence to back up these rigid recommendations around screen time.

The focus of parents' worries should be on the content, not on the time spent in front of electronics. "Digital technologies are part of our children's lives and are necessary in the 21st century," wrote the researchers.

This recommendation is similar to that of the American Pediatric Association after changing its policies in 2015. Previously they were also worried about screen time. Today, a more pragmatic perspective shifts the focus away from screen time, recommending that parents take an active position as it relates to technology. This means, for example, watching the content that is consumed very closely closely. Another strategy would be to access the internet alongside children, playing the videogame together, for example.

Increased access to the internet means increased contact with possible dangers, of course. The more time spent online, the greater the possibility for exposure. Data from TIC Kids, however, shows that while children that spend more time connected are more subject to coming across abusive content or advertising, they are also more prepared to identify and handle these risks.

Mediation by parents, in this context, is one of the chief protection factors, even when children spend significant time connected. Mechanisms of restriction such as software control and prohibition reduce the risks as well as the opportunities for learning.

In the debate around the protection of adults online, a key term is consent. Every person has the right to know about and authorize or veto any use of his or her information. But when we are talking about children, the debate is less clear. At what age is it possible to ask children for consent? In the United States, a law approved in 2008 (COPPA, mentioned earlier) fixed this age at thirteen. Before children turn thirteen, consent from parents is required for any use.

Are children aware of how their information is used? What about parents? Do they really know what is at stake for their children on platforms like YouTube, Facebook and advergames? Consent requires everyone to know what is going on.

The internet can seem like a hostile environment, but it is also a place where connections are made, identity is formed and a lot of interesting content can be found and used to stimulate learning. There are also wonderful apps and fun games, and very useful, fun and interesting videos for small children (and for parents who need a five minute rest).

But much like in the outside world, you can't just leave your child alone to explore an environment that, unfortunately, was made by adults for adults and is ruled by entities like Chupadados. This is why Gabi continues consuming content and playing games online, but always with supervision and on platforms that guarantee her security. And, of course, she doesn't know the App Store password.

Crédito da infografia: Daniel Roda e Tatiana Dias

Crédito da infografia: Daniel Roda e Tatiana Dias