STD(ata): non-consensual data transmission on dating apps

By Tatiana Dias and Joana Varon

In collaboration with Yasodara Córdova, Raquel Rennó and Camila Agustini

When you use dating apps, you give away (without knowing) much more than your body or heart

“I saw your profile on Happn,” he wrote. “I got interested and came here looking for you.” The message came from a stranger through Facebook chat. “I am not looking for adventures. I am a sensible and educated man.” He had never received a like or any sign that his feelings were reciprocated.

It was not the first time that Fernanda received unsolicited messages from people who said they had come across her profile on Tinder and on Happn. Dating apps, as you know, are based on reciprocity, meaning that contact can only be made among people who have mutually liked one another. In theory. It is not uncommon for a person from Tinder to appear ~mysteriously~ among your suggested friends on Facebook.

“In the past, guys have sent me a superlike or charm that I ignored because I was not interested. Then the guy stalked me on Instagram, liked and commented on many photos, tried to speak with me over chat...is it just me that finds this strange?,” wrote Flor de Lis, who made a public Facebook post describing what happened to her.

No. Many people think this is strange. Consent is a key principle in any caring or sexual relationship, but the patriarchy tends to diminish its value, minimizing consent to simple non-resistance. This thinking is what legitimizes much violence committed against our physical and psychic well-being.

In the digital realm, app developers operate under the same logic: using thin arguments to gain uninformed consent in order to use the data of those who consume its services, leaving a margin for a series of abuses. Dating apps are wonderful, but they collect much more information than they should, they give intimate data to ~partners~, capitalize on this and experience security breaches that put people’s privacy and security at risk. All of this without us knowing.

Just like sex depends on consent, a clear, free, informed and active agreement must govern the use of our data. In both cases, though to different extents, it is a question of self-determination. Entering the data orgy that dating apps impose upon us should be a conscious choice. But it is not working this way now. .

Latin Blood

In the early 2000s, people who used dating sites to find a partner or casual hookup were often seen as “desperate.” Today, things are different: 59% of people think that apps are a good way to meet new people, according to research conducted by the Pew Institute in 2015.

Latin Americans tend to accept new technologies with ease and the response to dating apps seems to have been even more positive. Brazil is the third highest-ranked country in the world for the number of Tinder users (behind only the USA and Great Britain). Just after come Mexico and Argentina. Buenos Aires, moreover, has the third highest number of Happn users.

It is no accident that Latin American countries have been chosen as laboratories to implement new aspects of Tinder such as Tinder Plus (tested in Brazil, the USA and Germany) and Tinder Online, the web version of the platform (of the eight test countries, half are in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico). 23% of Americans between 18 and 24 years old use Tinder. Around the world there are 26 million matches per day, 7 million of which are concentrated in Brazil.

“The majority of people with whom I have spoken think it is easier to start a conversation on an app than it is in real life,” said Rebeca, a screenwriter that conducted research about dating apps in 2014. Seeking to understand the motivations for using a dating app, she interviewed more than 50 users. She saw that among them, people felt more comfortable speaking about sex and fetishes that are generally tabu. “It is cheaper and more practical than going out,” she said.

Many dating apps also challenge stereotypes and gender roles, normalizing and facilitating sex with whomever. Even though cases of trans people being blocked have been registered, because of associations with prostitution simply because of their declared gender, the world of dating apps tends to be more permissive than other online networks. While social networks usually classify people as men or women, married or single, dating apps permit infinite genders, sexualities, preferences and relationship agreements - everything is possible just one click away.

Formulário de registro do Feeld. Se não entendeu nada, uma busca vai ampliar seus horizontes.

Registro do OkCupid, que também permite opção de não ver e não ser visto por pessoas hétero

One for love, two for money

The search for love and sex procreates apps, with alternatives from all of the sexual categories that you can imagine. Apps focused on the gay population, like Grindr, or the lesbian population, like Her orWapa, exist. For people looking for casual sex, there is Casualx, for people who thinks that two is not enough or want to open the door to fantasies, there is Feeld. For the people who have their eyes on a particular Facebook friend, there are apps like Poppin, which make matches among people who go to or have an interest in the same events. For people who don’t like the idea of meeting a complete stranger, apps likeFlert and Hinge use our networks as references and facilitate conversations among friends of friends. For people who are not keen on the window shopping aspect of some apps could choose Appetence, which only reveals photos after a bit of conversation.

In this fertile context, the industry of online dating moves a lot of money: it is estimated that in the United States, Match Group, responsible for Tinder, OkCupid and Match.com, brings in US$ 2 billion per year of revenue.

Our data feeds this industry. Different criteria, such as likes and preferences, distance and friends in common calibrate the algorithms that show or hide someone who would be potentially interesting to us or not. One of these companies business models is making people pay to increase their chances of matching. People are more likely to use a paid version of a dating app than of networks with other purposes like Facebook and LinkedIn. In the case of the apps, money can literally increase your chances for love.

Tinder, OkCupid and Grindr, which are among the most popular apps, have the option for users to pay to increase their likelihood of finding someone. Beyond removing the ads, premium plans increase your popularity artificially, increasing the number of exhibited profiles or the limit of likes. They also give you the chance to go back and see a profile that interested you but that you let pass with your anxious fingers in the search. The rules around who shows up for whom, however, are not very clear. Who is determining your potential crushes?

Pedro, 31, decided to test out Tinder’s paid service, which highlights your profile and removes the limit on the number of likes. After getting accustomed to one or two matches per week, he was surprised with 40 in eight hours. After the paid boost, however, the matches kept happening with greater frequency. “Or I was not showing up for anyone or the app just suppressed those who don’t pay,” he said, questioning the way people are distributed on the app.

The businesses clearly do not thrive solely on these paid accounts. Many people prefer to use the free version of the app and see ads. When the product is offered for free, we know that the user is the product. Precious data about people’s behavior while they are flirting is provided to advertisers, marketing firms, researchers and commercial partners.

Swinging without rules

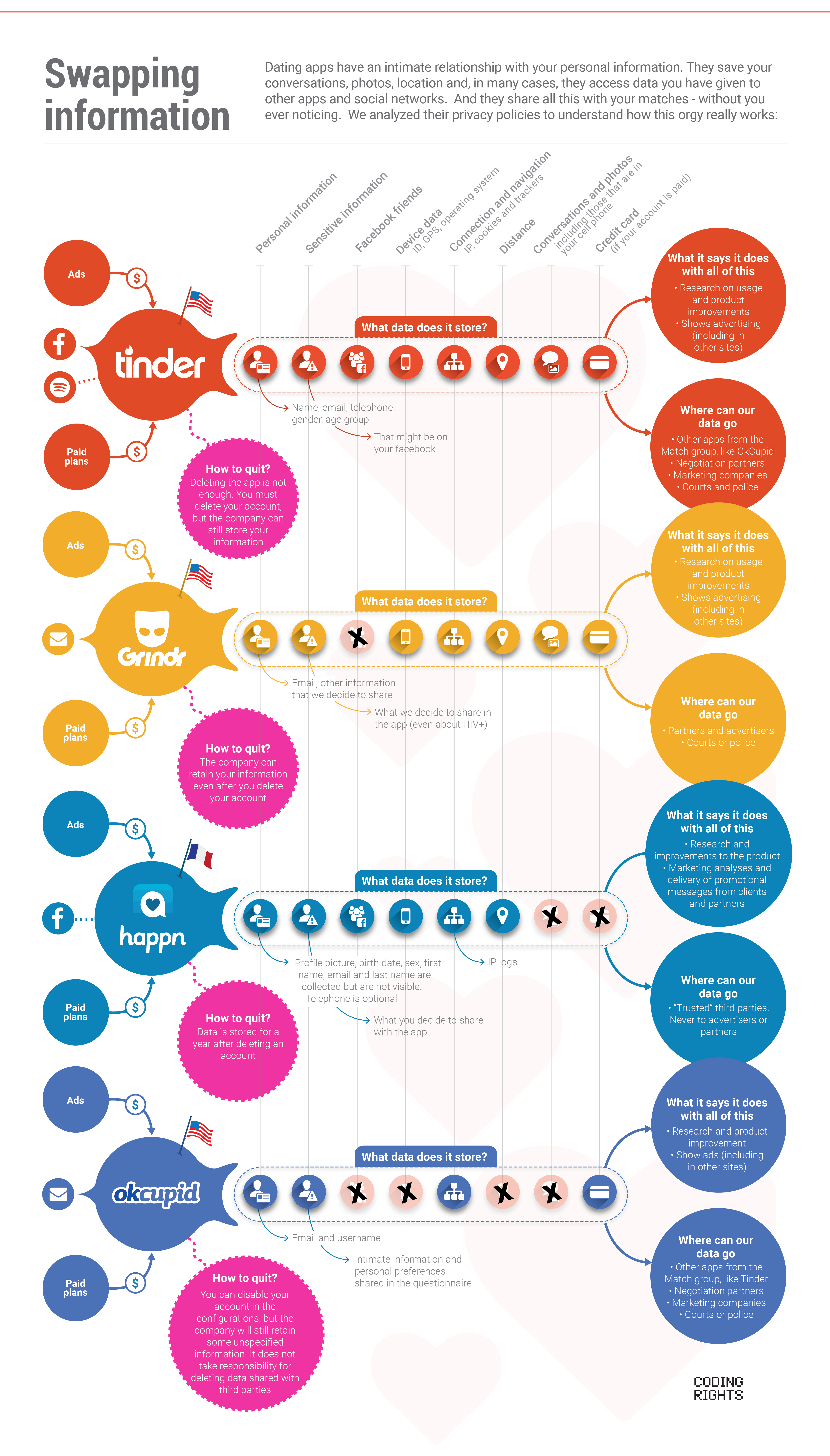

The four apps that we analyzed - Tinder, Happn, OkCupid and Grindr - release information about their users to partner organizations. This means, for example, that users’ preferences, behavior patterns, hours connected and other information can be analyzed and utilized by other companies for diverse purposes. They go from showing direct marketing to the sale of a package of information to a data broker, a business that is dedicated to commercializing and analyzing large volumes of data.

All of this information gathered can be made available even if you quit the app and delete your account. This is because, by saving our data, photos and conversation history, companies can keep earning money with profiles they make based on our data, even after we stop using their services.

Crédito da infografia: Daniel Roda, Joana Varon e Tatiana Dias

Crédito da infografia: Daniel Roda, Joana Varon e Tatiana Dias

A study published on Monday the 12th by Privacy Brazil analyzed the privacy policies of 14 dating sites and apps and made a ranking based on transparency and clarity criteria. The only site with a positive result was Coroa Metade. The others had negative scores based on their policies of consent, clarity about risks or data sharing practices, and the requirement of a login through Facebook or use of a profile image. The ranking is available here.

This is not a new problem. In October of 2011, Jonathan Mayer discovered that OKCupid sold information about its users to marketing companies like Lotame. This included data that people probably would not like for others to know such as income, relationship status, religion, and drug use. Until 2010, OkCupid, which advertised with the slogan “beyond selfies, substance,” shared with commercial partners responses to private questions like “have you ever had an abortion?”

OkCupid saves and can share the intimate information and personal preferences that you share in the questionnaire

In 2016, Happn was accused of leaking user information. Research done by Sintef at the request of the Norwegian Consumers Bureau showed that the French app shared user data with the marketing company UpSight. The practice violates the terms of use of the app, which state that they will not share personal data with other companies. Happn confirmed that they used the tool Upsight to understand how the app is utilized and data is “made completely anonymous when processed.”

Tinder accesses and can utilize photos and personal information that are on your Facebook profile, and those on your friends’ profiles also

Another piece of research done by Wired showed that apps like Tinder, Happn, Match.com, Bumble and others leak information such as Facebook IDs, images and data about your location. The analysis was done based on information transmitted from the servers on its users’ cellphone apps. Happn, for example, only shows the user's’ first name, but in the information packages that are shared between the servers and celulares, leaks Facebook IDs.

You can get an idea about the scope of the damage if this information ends up in the wrong hands, or worse, if it becomes public. Just remember what happened when a leak occurred at the dating site Ashley Madison. The platform was created to facilitate extramarital relations. The leak exposed 33 million users. Consequences for this error included persecutions, harrassment and even deaths.

Happn has a more restricted policy, but it saves precise geolocalization data and keeps information for a year

It is our right to know what of our data is being saved, ask for a correction or, in some cases, delete it altogether. The data protection rights of many Latin American countries, including Mexico, Argentina and Chile, guarantee this right.

In Brazil, even though we do not have a specific law protecting our data, the Internet Bill of Rights speaks directly to this issue. In Article 7 of subsection X, it guarantees the right to request that personal data given to any app be deleted. The text also stipulates that if the data are collected within Brazil, Brazilian legislation applies, even if the app was developed in another country.

The region has not made use of strategic, collective litigation to test the jurisprudence and discover how and when our profile data can be deleted. This process would force platforms to take more transparent and secure measures around our data. For now, we can take some precautions when looking for matches.

Encounters and missed encounters

Some people have also used our data beyond what we consented to, extending far beyond the flirting game. It is not uncommon that screenshots with users’ profiles be posted in forums and pages for random evaluation or appreciation. There are also many pages dedicated to making fun of users, exposing photos and private conversations without hiding people's identity.

The instagram profile Tinder Nightmares reminds us that dating apps can have many cool people, but also a lot of problems. On it you will find screenshots from Tinder with the identity hidden but with strange and oftentimes aggressive, prejudiced comments or threats. In one of the screenshots, for example, a guy asked: “what do a personality and an orgasm have in common?” She responded: “I don’t know.” And he said: “I don’t care whether or not you have either one.”

The worst is that this ridiculing approach goes beyond the boundaries of the app and ends up on other networks. Some dating apps demand a Facebook login or allow for connection through Instagram or Spotify, for example. When this happens, clearly it is easier for someone who matched on the platform find the person on other sites, as happened to Flor and Fernanda. But this can also happen even when accounts are not connected. Since WhatsApp is owned by Facebook and the networks exchange information, as soon as you take the conversation to WhatsApp, you will probably receive a friend suggestion for that person on Facebook, even if the date was a fiasco.

Because of their business models, companies do not have much interest in restricting the circulation of this information or of our profiles. A large segment of the users are also not interested in respecting one of the apps’ most basic concepts: reciprocity.

A Brazilian publicist, for example, had a false profile created on Tinder after she declined an invitation to go out with a photographer that she met on Happn. They started a conversation on the app, but she did not carry it forward. Left uncomfortable, the guy created a fake profile of her on Tinder, using a real photo and presenting her as a prostitute. She discovered this later when she started to receive WhatsApp messages from people interested in her services. The case was reported in an event report at a Women’s Defense Police Unit in São Paulo.

By forcing conversations on other networks, without respecting the “no” or silence coming from the other side, these users show that the do not care in the least about consent. And this practice has a name: stalking, in other words, persecution online in an obsessive and persistent way.

The apps have mechanisms to avoid abuses, the chief of which being only allowing encounters when the interest is mutual. But in some cases the trap is also technological. Programmers created, for example, a tool that allows anyone to research who is using Tinder and to find out their last localization. For US$4.99, Swipebuster shows who has a profile on the app and filters the results by name, age, gender and location. The results appear with a foto under the word “busted. You do not have to be on Tinder to access the results. You just have to go get them.

Its creators used Tinder’s API, which allows anyone to create apps that are connected to the software. The idea of Swipebuster was also to call attention to the lack of security. “There is a lot of data that people have no idea is available,” the programmer who created the app told Vanity Fair in 2016, around the time that the app was launched. Tinder said that there was no security issue, as the available information was the same as what was public on the user profiles.

It might be surprising to have your name indexed by stalkers, who also have access to your localization, too, but things can get worse.

On Grindr, a dating app primarily used by gay males, any person has access to the exact location of another profile even before starting to flirt. The computation security researcher Nguyen Hoang, from Kyoto, Japan, showed that using trilateration, a mathematical method to calculate position, it is possible to determine the location of any user. Just go to three different points and calculate the distances. Grindr recognized the problem and made it possible to deactivate the location sharing function. It also made this the default setting in countries with a history of violence against the LGBT population, like Russia.

You don’t have to leave the game, but proceed with caution

To find your crush in a more secure way it is important to understand who is participating in the data orgy and its rules. From there, you can decide if and what what you want to reveal about yourself. Since you can’t flirt completely anonymously, it is a good idea to reveal who you are slowly. Some things to consider:

When creating your profile on the app

-Try to protect your identity. Your username does not have to be your full name. Do not say where you live or work. Know that if the app that you chose is based on location, this information is easy to discover.

-Do not connect personal accounts. If your favorite app only accepts login via Facebook, or if you are going to connect other accounts like Instagram, it is worth giving a look at the information that you have public there as well as at your privacy configurations.

-Avoid using the same photo as your use on other social networks. If you prefer not to link with your accounts on other networks, remember to choose specific photos for the app. Do not use the same images that you use in your profile pictures for other social networks, for example. Some people like more mysterious photos, which can guarantee you pseudo-anonymity.

-Do not share your telephone number or email. If you want to login with email, create an alternative email account just for this.

In the search for the crush

-Put a password on your phone. At the end of the day, you do not want other people stalking your crushes. Encrypting your phone makes it even more secure.

-Never open annexed links sent by strangers you meet on the platforms. They can contain viruses or malware that could be used to steal your data. (By the way, don’t do this off of dating apps either!)

- If you clicked and things are starting to get interesting, leave the chat of the app. While messaging apps have evolved a lot around privacy and security, dating apps do not encrypt conversations. Invite crushes to take the conversation to an app where your words and your nudes can be encrypted and later destroy themselves. We recommend apps like Signal, Wire or the secure chat feature on Telegram, which has a timed destruction feature. To learn more about how to send safer nudes, check out our zine Safer Nudes.

-Be careful when using your account on public Wi-Fi networks. These connections are easily monitored by third parties (called traffic sniffing). If connecting is unavoidable, use a VPN.

Before meeting up

-What about doing a little stalking yourself? You do not need to get obsessive, but the data that is out there can also help you avoid a dangerous trap. Sneak a peek at your crush on your favorite search engine and on social networks.

-Let a friend know where you are going. Send one of the links that you found when you were stalking the date to someone you trust. When you can, let them know that everything seems fine. If there was no time to check in, at least keep an app running on your phone like "Braços Dados". Developed by our partners at Genero e Número, the app lets women send messages to a trusted network when they feel at risk.