They are stalking you to calculate your credit score

By Tatiana Dias and Igor Natusch

Collaborated: Flávio Siqueira, Joana Varon e Natasha Felizi

Translation: Trajano Pontes

Your work, your friends, your social life. Access to finance is determined by criteria that go well beyond the money going in and out of your bank account.

"You know Black Mirror, right? That's just what we do here", one suit-and-tie executive, definitely over 60 years of age, told me at the leading event dedicated to Brazilian finance startups. Dozens of companies were there to exchange experiences and present to the market new technologies related to our money. I was there to understand specifically how some of them decide which among us can take a loan or not.

He was not joking when he compared the services his company provides to the technologic dystopian series. He referred specifically to the first episode of the third season, the one in which people have a score – or a rating – that goes up or down according to their behavior, reputation and social activities, score on which they depend to get jobs, credit, friends.

I wanted to understand better how that worked. The company in question is one of several that operate in Brazil with credit scoring – that is, they help lenders assess whether it is worth or not to lend money to someone. Each consumer has a grade that says whether he or she has a good chance, or not, of honoring a loan. This grade is generated by proprietary mathematical formulas that take into account our bank history, past debts, age, gender, profession, social circle, Facebook activities, recent purchases and every kind – every kind indeed – of information about us available out there.

To accomplish that, the main product of the company in question, as the website puts it, is the "sale of information." Bragging about having its own 10-billion-record database, the company catalogs CPFs (individual taxpayer registry identification) of 167 million Brazilians. There are 120 million phone numbers as well, but the information collected goes far beyond that. These data come from business partners (who use their scoring service to analyze consumers), purchased databases, social networking, circles of friends, among other sources.

This information combined is enough to tell if a person is likely to spend more, less, take out a loan and honor the debt. The level of detail goes up to marital status, which can be determined based on behavior and purchase history. "Being single is good, but it's bad for the score, right?", the executive told me with a smile, explaining that not having a fixed partner can be frowned upon by potential lenders. That is why the score goes down.

According to him, the rationale for such rich detail is that, for example, people who otherwise would not have access to finance through traditional means – like people who do not have a fixed job or are unbankarized – may score high if they follow certain standards. He also told me that it is possible to increase one’s credit limit by authorizing the company to collect more information about oneself through partners or by referring friends on social media. That way it is possible to know with whom you walk – and if you have a social circle of potential good payers, lenders understand that you are probably one too. "Birds of a feather flock together," said the executive. If your friends are flat broke, well then probably the banking system that feeds on this information thinks the same about you.

Not on the (credit) list

All that the lawyer and legal advisor Flávio Siqueira Júnior wanted was to buy supplies to renovate his home. However, he ended up facing an unexpected problem at a Leroy Merlin store in Sao Paulo in February 2016. When he finished the purchase, an attendant suggested him to make a private label card from the store. Seduced by the installment scheme offered, he agreed. After registering, however, he was informed that his request had been denied. Siqueira failed to reach the minimum score required for the card to be issued.

"At that time, I did not hold a credit card or even use the authorized overdraft limit, nor had I entered into any kind of debt with financial institutions or installment payment plans", he assures. Thus, he had no registered debt. Intrigued by the refusal, he was willing to clarify, from a legal perspective, the criteria that had led to his credit denial.

Siqueira sought contact with Serasa Experian, the company responsible for the credit assessment, trying to understand what data was stored and what were the variables taken into account when assigning his credit score. After mailing the required request, he received answers that were not very clear, where the company merely said that it "provided to lenders, upon request and according to contractual terms, data collected from public and private sources, all of which were legitimate and lawful."

Incited by the Coding Rights team investigating the various manifestations of the Chupadados, and outraged at the lack of transparency, Siqueira filed a Writ of Habeas Data, a judicial remedy that allows any citizen to request the disclosure of data that government agencies or companies have on him/her. The idea was to force, through the Judicial Power, the disclosure of information in order to at least understand what data were used and to which a low score could be attributed. Not even then were information released: more than a year later, this specific credit denial is still in force, and Siqueira is still unable to understand what led Serasa Experian to treat him as a potential bad payer.

A score on the forehead

The situation lived by Siqueira is not exceptional. The financial assessment industry is one of the most promising in the market – and is run by companies of all sizes, including banks, credit protection bureaus such as Serasa Experian and finance startups, the so-called fintechs. All of them combine diverse data and methodologies to provide different answers to the same question: what is the default risk of this person?

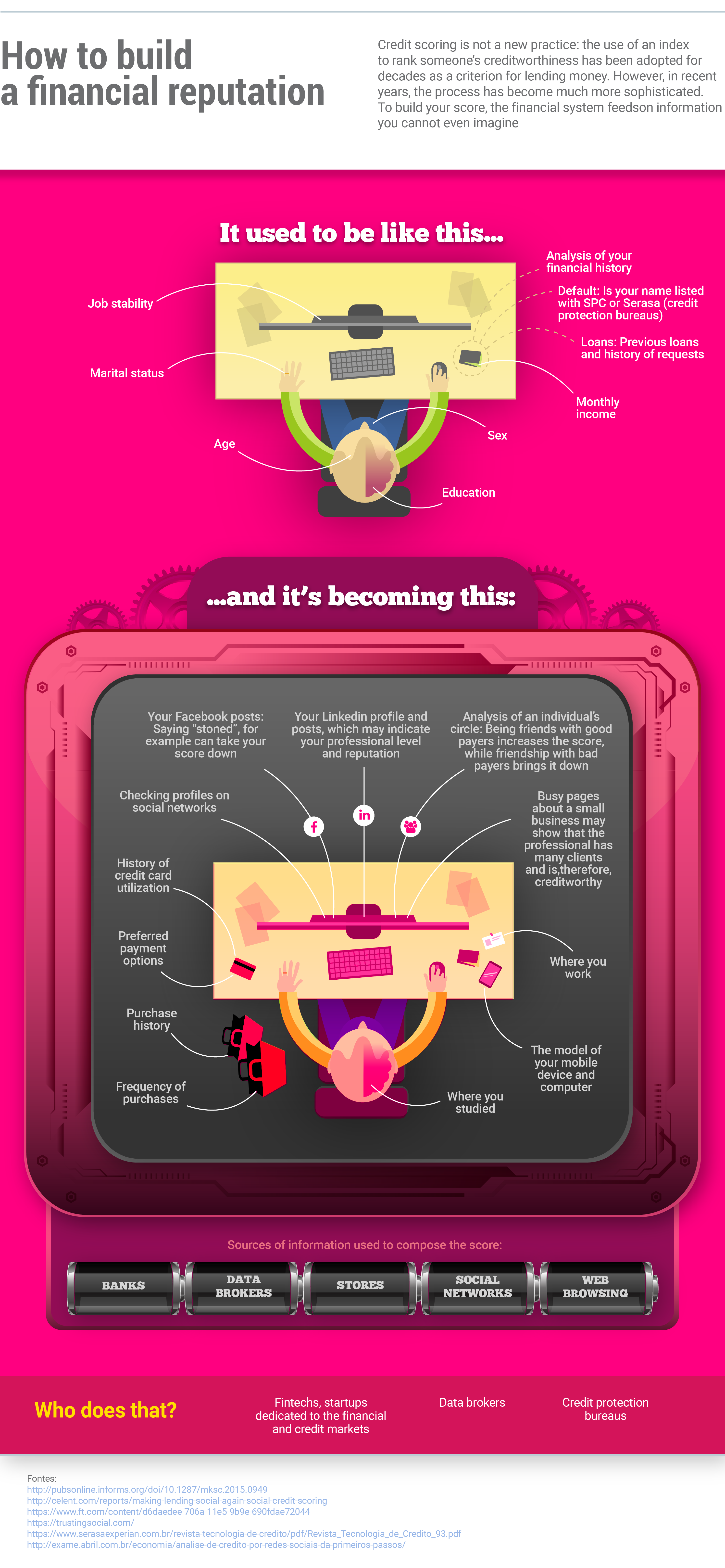

This score will define whether the person will be entitled to take out a loan, to finance a car and whether he or she will pay more or less interest. You most likely already have that score yourself. You just does not happen to know what it is – much less, how it was built. Salary, employment stability, previous loans, default history, and data from the Chambers of Commerce are among the obvious data used to compose the score. But in order to get more accurate assessments, companies source their databases with as much information as possible, crossing and relating data and making a number of value judgments.

Over time, the data considered relevant expanded from mere economic aspects as

to increasingly incorporate everyday and behavioral aspects - a

process that was accelerated by the explosion of social media. A LinkedIn

profile, for example, can reveal the customers engagement degree of a

company. A number of Facebook posts on hangover can compromise a reputation.

Having many friends who are bad payers or do not have a fixed job may indicate

that, well, your financial profile may not be as reliable as your paycheck

indicates. On the other hand, owning the latest iPhone or an expensive computer

can boost your score.

Nevertheless, you are not informed of any of this.

The finance stalkers

There is nothing to prevent financial companies from using personal information or social media data to do credit analysis. There is nothing either to set limits to the relating of information or to the finance stalking. Nor there are means to ensure that the consumer has access to information about the criteria used in the preparation of his/her score, or that the consumer may change his/her reputation or correct some misinformation.

"People do not understand what a scoring system is," says Rafael Zanatta, a telecommunications specialist at the Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor (Idec) (the Brazilian Institute of Consumer Protection), who researches the performance of these companies and advocates changes to the system. His main criticism is on the lack of transparency: it is not clear to the consumer what criteria were used in the preparation of his/her score. As a result, it is very difficult to get rid of the deadbeat stamp that someone may have printed on his or her forehead (although invisible to the very person).

By Daniel Roda and Tatiana Dias

By Daniel Roda and Tatiana Dias

The complexity of the system is one of the reasons why the consumers are not informed about almost anything related to their score. To understand how this works, one must first understand who the stalkers, that are highly paid to scour people's lives searching for potential deadbeats, are.

To analyze financial, social and behavioral information, many credit institutions turn to data brokers, companies that collect, process and sell personal information on consumption profiles. Data brokers search through government sources, social media, databases of other companies and any corner of the Internet where useful information may be available to build databases of personal information. Separately, the information collected have little value; it is when they are assembled and organized into standards that they become more interesting to the companies that hire such services. The list of clients is wide, ranging from financial and insurance companies to telecommunications companies, election campaigns and even government agencies.

Present in several countries, these companies are unknown to the public and mainly render their services to the marketing, strategy consulting and financial industries. The idea is that, grounded on a massive amount of information on people, it is possible to generate marketing insights, standards of behavior and assess the creditworthiness of consumers. Serasa Experian and Acxiom are some of the data brokers that operate in Brazil, selling strategic analysis based on people's data and information.

Goodbye, banks; hello, fintechs

These companies make big money. According to the newspaper

Valor Econômico, revenues of the credit data processing industry in Brazil

amount to approximately R$ 3 billion per year – and they may double in the span

of a few years.

Because of its growth potential, the credit scoring and assessment system

surpassed the traditional market – banks and stores, for example – and reached

the fintechs, which rely on technology as a differential advantage to develop

their products and services. Many of them have developed specific credit

analysis tools, based on Big Data and social media monitoring, for example. The

goal is to produce a faster, more efficient and comprehensive analysis.

Geru, for example, has developed a "proprietary

credit assessment model". The company claims that it "combines data and

documents provided by loan applicants with information from various sources of

information." According to the company, there are hundreds of criteria and a

"rigorous process that culminates in a credit score." This score, explains the

company, is related to the grant or refusal of the loan and to the interest

rates. When we enquired the company about the subject, it argued that its

spokesperson was traveling.

Lendico, a company that says to perform a careful analysis and operate with a lean structure, works in the same model. Under the slogan "forget the banks," it promises loans without bureaucracy and with lower interest rates. It seems tempting, and it is; but the credit analysis model, tested by the Chupadados team, is not at all clear. We submitted the same credit application to a bank and to this fintech and the result was that the same loan was granted by the ordinary bank and refused by the fintech's analysis. We asked why. Even with the answer, we do not know yet:

"As to our assessment, there are a number of factors to be considered. One of them is the credit score. But there are other ones, such as the debt-to-income ratio represented by the repayment installment, conflicting data, listing with credit protection bureaus and payment history," explained the company, through its press office. Lendico says that it relies on information sent by the client "that are public and that he or she authorizes us to consult". "All such information are objective, clear, true and easy to understand, and are only used to the extent necessary to assess the economic status of the consumer."

The financial intermediary Bom Pra Crédito runs a different model. It suggests

that

the person applying for credit should send a selfie, which will then be

processed by facial recognition programs. The photo also serves to provide

information about the device used and geolocation, which can then be related

with the database to reveal where the consumer goes, what products he or she

purchases and whether the expenses he or she makes are compatible with his or

her apparent income.

In principle, there is nothing illegal with relating these pieces of information. The market sees this kind of stalking with good eyes: by reducing risk, it is possible to allocate investments more efficiently and give more stability to the financial system. Another argument favorable to the practice is the possible financial inclusion of less wealthy sections of the population and of those who would not have access to credit from traditional lenders. An entrepreneur who has no fixed income, for example, can have access to a loan upon verification of the intense movement of clients on his/her Facebook page.

The problem is that classifying a person as a potential deadbeat in an obscure process may have impacts greater than the simple denial of a credit card. Insofar as it deals with a range of personal data, many of them sensitive, credit scoring may eventually have not only unfair but also invasive and harmful effects on the consumer. A decision taken by credit assessment companies can have effects that go far beyond a purchase that is not authorized or an investment that does not take place.

Underlying prejudices

In Brazil, credit scoring is not regulated by specific legislation. There are, however, two sets of limits: those provided for in the Consumer Defense Code and in the 2011 Positive Credit Registry Law.

The law authorizes institutions to have a record of the payment history of their clients and, although it prohibits the use of excessive or sensitive information, such as social and ethnic origin, health condition and sexual orientation, its application to credit scoring is limited – after all, the data analysis process is not transparent. The Consumer Defense Code and the Positive Credit Registry do not detail how citizens’ information should be processed.

For Danilo Doneda, a researcher on privacy and a professor at the Faculty of Law of the State University of Rio de Janeiro, there is no incentive for Brazilian companies in this industry to be transparent for two reasons: being more transparent does not bring financial benefit to the agency and informing the consumer and society about the criteria used is not, from the legal perspective, an actual binding obligation yet.

Doneda believes, however, that the approval of the personal data protection draft may have the effect of "raising the bar" to the market – that is, creating a goal that forces companies in the industry to adopt more transparent practices. "Regulatory action is needed because some companies may have a clearer view on transparency but, as competitors in the market adopt bad practices without consequences, the tendency of the players is to jointly adopt a worse practice."

Researchers and entities argue that consumers should have access not only to information on them, but also to the weight that each piece has in the composition of the score. Current practice is obscure.

"There is no information on the methodology used and the algorithm is considered a trade secret," says Kimberly Anastácio, of the Private Law and Internet Research Laboratory at the University of Brasília (UnB). Due to the lack of transparency, it is not possible to know if personal or sensitive aspects are weighed when an agency refuses credit to someone.

"There is no way to be sure that prejudicial actions are not happening during this analysis"

Kimberly Anastácio, professor at University of Brasília (UnB)

Consumer protection agencies advocate that companies should disclose not only the data they use to credit score someone, but also the weight of components – and this is one of the legal battlegrounds. Who should win: the protection of industrial property or the right of the people to have access to information that affects their financial lives? For the time being, the former one has prevailed.

What is bad about the positive credit registry

The

2011 Positive Credit Registry Law

provides that banks and other institutions create a register of consumers

who have a positive reputation. Several of them offer the alternative, which

works in an optional fashion: you register only if you want. The same law also

establishes rights for citizens regarding the type of information that can be

collected, transparency duties and the power of individuals to rectify them. The

law expressly prohibits the collection of "excessive data" and "sensitive

information".

However, Bill 122/2017 is currently under discussion in the Chamber of Deputies

of Brazil. It changes the functioning of the system by including people

automatically in the register and authorizing financial institutions to exchange

information. More than 40 entities opposed the bill, arguing that, if approved,

it would eliminate the possibility of consumers' choice increase banks' harassment of people and create a huge database, that would

comprise data on people that would much exceed information of a financial

nature.

If we think about the enormous concentration within Brazil's bank industry –

where only five institutions trade 80% of the country's cash –, one can also assume the concentration of information in the hands of the few.

In a heated market, with startups popping up – and being bought by the giants –,

you can imagine that the scenario of one huge single database is not far from

reality. If this database attributes to us a personal score that gives us access

to credit – through good behavior, good network and a good job –, the Black

Mirror scenario may not be that far apart.

In China,

the government has announced that such a system tends to evolve into the

so-called social credit system. That is, in the same way that data brokers

draw profiles of good or bad payers, there would be a score evaluating what kind

of citizen you are, whether you are sincere, trustworthy, patriotic, etc. For

the time being, this type of registration is optional, but will be mandatory

from 2020.

Currently, eight private companies are developing algorithms to aid in the

implementation of this system, one of them being the developer of WeChat, the

WhatsApp-like application used in China, which has more than 850 million active

users. Another one is a partner of Alibaba, an e-commerce giant that has already

stated that it evaluates people according to the products they buy. Friendship

in social media and types of interaction in those platforms also have an impact

on social credit, which, if high – in a curious way –, will fuel consumption and

"good behavior" but also tend to evolve into better offers of services and

products.

What the STJ (the Brazilian Superior Court of Justice) says

Brazilian legislation does not define credit scoring. But a 2014 decision by the STJ (the country’s highest appellate court for non-constitutional questions of federal law), rendered in connection with a series of lawsuits seeking indemnification for moral damages filed by consumers outraged at the existence of a scoring system, established interesting parameters:

1. What it is: For the STJ, credit score is a method for risk assessment from statistical models – a procedure that relies on databases as a source but is not a database in itself.

2. It's legit: The practice is considered lawful and individual consent is not required for someone’s score to be calculated.

3. You have the right to know: According to the decision, the consumer may request access to the source of the data and the personal information taken into consideration.

4. To the point: Everything must be clear and precise so that the consumer is able to check the accuracy of the data and rectify them.

5. No, they can’t: The decision prohibits the use of excessive data – sexual orientation, religion or ethnicity cannot affect the score, for example. However, clarity on what excessive data are is still lacking.